Remembering Nathan Hale

"Even the distance at which the Almighty hath placed England and America, is a strong and natural proof, that the authority of the one, over the other, was never the design of Heaven."

-- Thomas Paine, Common Sense (1776)

Independence Day is here, and with it I'd like to remember someone who embodied the spirit of Independence as much as any American, although (unforunately) most Americans today probably do not even know his name.

Nathan Hale, Revolutionary War Hero

Nathan Hale was born in Coventry, Connecticut, on June 6, 1755, and was little more than twenty-one years old(!) when he was hanged as spy, by order of the British General William Howe, in New York City on September 22, 1776.

Hale's patriotism manifested itself sooner than that of most of his peers. Soon after news of the battle of Lexington and Concord (April 19, 1775) reached New London, Connecticut (where Hale was living at the time), a town hall meeting was called. At this meeting, the nineteen year-old Hale rose to speak, where he implored "Let us march immediately and never lay down our arms until we obtain our Independence." It is believed that this may be the earliest record in which the word "independence" was publicly spoken in connection with the American Revolution.

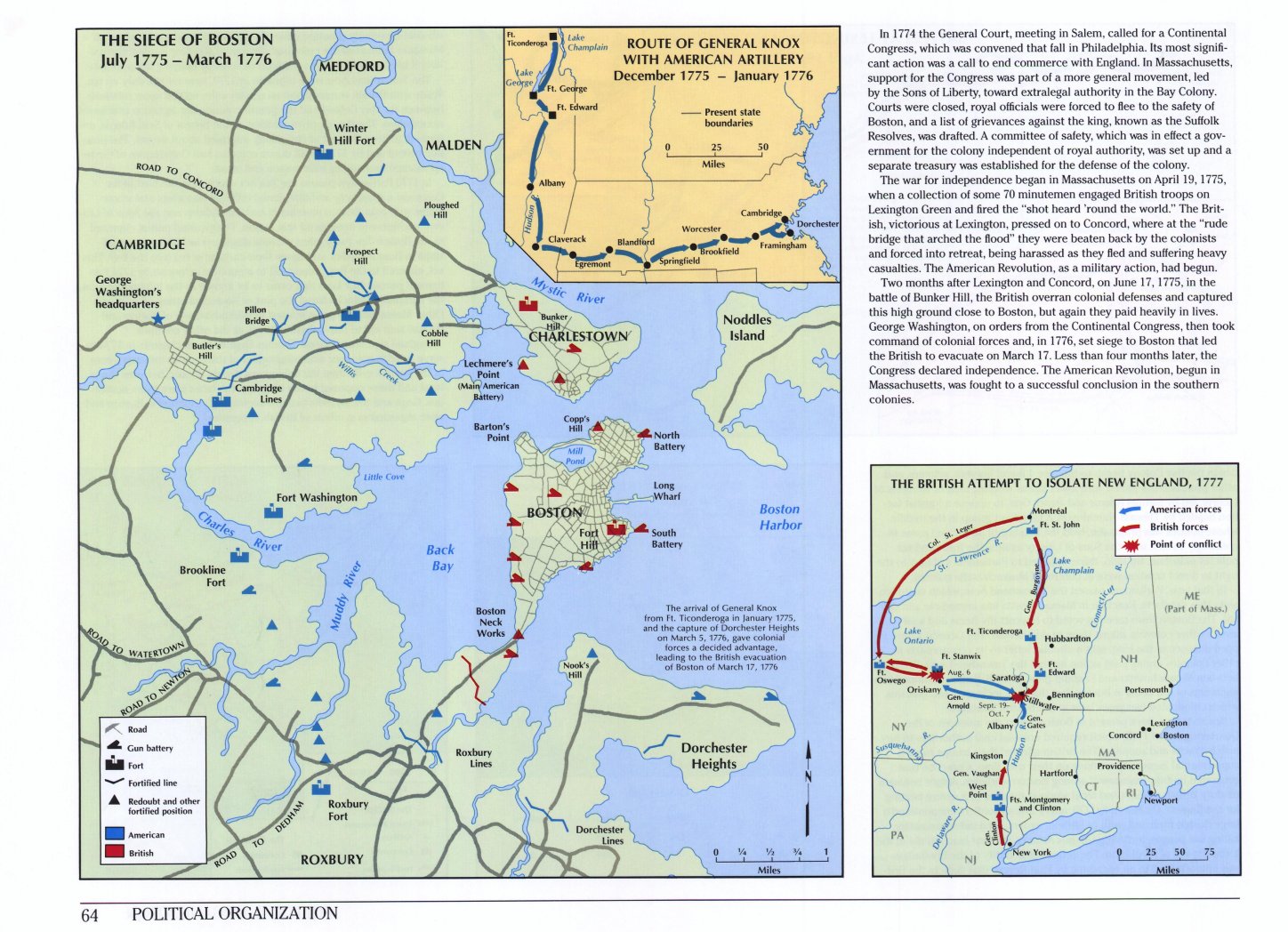

Hale was commissioned as a First Lieutenant in the Seventh Connecticut regiment in July, 1775. On September 14, 1775, the regiment was ordered by Genereal George Washington to proceed to Cambridge (Massachusetts), where they made their camp at the foot of Winter Hill. Here they were able to command the passage from Charlestown, one of only two roads by which the British could march out of Boston, and they remained here until the following spring, laying siege to the British. On March 27, the British evacuated Boston, and Washington redeployed most of his troops to New York City, where he anticipated the next British attack.

Fire destroyed over 25% of New

York City on September 21, 1776

In New York, however, General Washington met with decidedly less success than in Boston. On July 3, 1776, British troops landed on Staten Island. Over the next six weeks, their numbers increased to about 32,000. On August 22, General Howe began transporting troops from Staten Island to Long Island to meet the American forces in battle. Washington decided to defend Brooklyn Heights by digging in around Brooklyn Village. The much stronger British force soon overwhelmed Washington's troops, who were forced to retreat across the East River to Manhattan on the night of August 30. On September 13, General Howe followed the Americans across the East River and landed at Kips Bay (near what is now Murray Hill, in the East 30's of Manhattan). Washington was forced further north to Harlem Heights, where a brief skirmish, now known as the Battle of Harlem, was fought. The battle proved to be a brief respite for the Ameriacns, with several hundred British light infantry being badly mauled by Colonel Thomas Knowlton's Connecticut regiment. Yet despite the brave showing, Washington's forces were badly outnumbered and Washington was forced to begin a full retreat to White Plains on October 12.

It was in the midst of these skirmishes around New York City that Nathan Hale met his courageous and untimely end. On September 6, Hale volunteered to undertake a "spy" mission to gather more information about British troop movements in and around New York City. William Hull, who would later command the fort at Detroit as major-general and who was Hale's classmate at Yale, warned Hale about the dangers that he was about to undertake. Hale simply replied "I wish to be useful, and every kind of service necessary to the public good becomes honorable by being necessary. If the exigencies of my country demand a peculiar service, its claim to perform that service are imperious." These are the last recorded words of Hale's, until he spoke just before his death.

In the second week of September, he left Stamford, Connecticut by boat and landed near Oyster Bay, Long Island. He directed the boatman to come return for him on September 20, and then made his way into New York City where he made his "inquiries" and observations. September 20th found Hale back at Oyster Bay, awaiting for his boat ride back to Connecticut. He thought he saw the boat, signalled to it, but -- unfortunately -- the ship he saw was a landing boat from a nearby an English frigate, which lay screened behind the bay. Hale gave flight, but was soon captured, and the information on his person betrayed his purpose and mission. He was taken onboard the frigate, and taken back to New York City under heavy guard.

Turtle Bay (c. 1840) at the foot of

what is now East 49th Street. The

Beekman House is in the background

It was a bad day for an American spy to land in New York. Hale landed while the city was in terror due to the great fire of September 21, which burned down nearly a quarter of the town. The English had assumed (rightly or wrongly) that the Americans had set the fire. Two hundred people were sent to jail upon suspicion of being arsonists.

There was no trial. Hale was summarily sentenced to be executed the following morning, on September 22. He was interred for the night in the greenhouse of Howe's headquarters, a place known as the Beekman House at Turtle Bay. This house (which would have been on the present-day corner of 1st Avenue and 51st Street) was still standing until a few years ago. The next morning he was marched out to the place of his execution, near the present intersection of East Broadway and Market Streets, on the Lower East Side, close to the foot of the (present-day) Manhattan Bridge. It was here that his executioner asked him if he had any last words. Hale's immortal reply was:

I regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.

It's believed that a play Hale read while at Yale, probably Joseph Addison's Cato, was the inspiration for his final words.

1 Comments:

At 5:40 PM, oakleyses said…

oakleyses said…

burberry pas cher, nike outlet, nike roshe, christian louboutin shoes, louis vuitton outlet, oakley sunglasses, polo outlet, oakley sunglasses, longchamp outlet, louboutin pas cher, nike air max, ugg boots, christian louboutin uk, polo ralph lauren outlet online, louis vuitton outlet, gucci handbags, ray ban sunglasses, louis vuitton outlet, air max, michael kors pas cher, christian louboutin outlet, uggs on sale, ugg boots, louis vuitton, christian louboutin, longchamp outlet, oakley sunglasses, prada outlet, tiffany jewelry, replica watches, ray ban sunglasses, nike free run, tory burch outlet, ray ban sunglasses, polo ralph lauren, tiffany and co, prada handbags, chanel handbags, nike air max, jordan shoes, louis vuitton, kate spade outlet, replica watches, longchamp pas cher, oakley sunglasses wholesale, jordan pas cher, longchamp outlet, cheap oakley sunglasses

Post a Comment

<< Home